“What programming language should I learn?” is a perfectly reasonable question. You might have asked it yourself. Almost every answer to that question you’ll get is bunk. The one that isn’t, sounds something like, “It depends on what you want to do.”. Which is, while not complete bunk, still very bunk-ish because it isn’t really an answer. The vast majority of people asking this question don’t know what they want to do, other than “program a computer” in some sort of abstract sense that implies they will have a job or become a billionaire if they are successful. The most recent time I’ve heard this question asked, was on Reddit, and the answers were, as expected, bunk. But it stuck with me, so I started to think about how to answer it in a way that isn’t worthless. This is what I came up with.

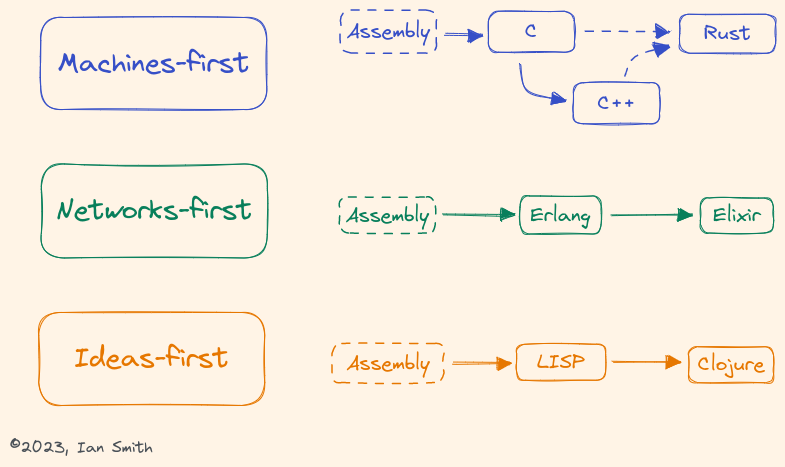

A person who wants to write a program has to choose one of three mental/conceptual systems of abstracting the world. This isn’t optional, but it might be an unconscious or tacit decision based on why you want to write a program.

- Option 1: Machines are in the primary position of importance and people and ideas have to conform to what machines permit you to get them to do. You should pick this option if you want to write software for making machines do stuff with the most control and efficiency possible.

- Option 2: Networks are in the primary position of importance and the ideas and people and machines all have to conform to how the network defines the world. You should pick this option if you want to write software that takes advantage of the network to the greatest extent possible.

- Option 3: Abstract ideas are in the primary position of importance and people and machines have to conform to the constraints and requirements created by these abstractions. You should pick this option if you want to write software that has the most flexibility to deal with the unforeseen or unknown, or software that adapts to it’s environment over time.

Programming languages rarely pick one of these options when they are created, but they do tend to favor one above the others. You might be asking, “what about putting people in the primary position?” That would be great, but there are no programming languages that do that. There are some that put the programmer’s needs at a higher priority than others, but no language that I know of cares about what non-programmer’s think or want. You should write one.

If you can figure out what is most important — controlling the machine, leveraging the network, or being adaptive to change — then you can figure out what languages you could learn. In my opinion, that list is a lot smaller than people make it out to be.

If you pick Option 1, it is very hard to not learn C and once you have learned C, it is very hard to not learn C++. These are powerful, well known, and if you are good at them, you’ll be able to find a job that pays the bills (and then some) almost anywhere, in almost any industry. Operating systems are written in C; the compilers, interpreters, and virtual machines for other languages are written in C; so are the drivers for anything you plug into your computer, from your thumb-drive to your graphics card to you printer; so are games and programs for all kinds of computers. And C is the de facto API for getting programmers writing in any language to communicate. When you know C you are an astromech droid; any problem you encounter, you can solve, you can talk to anyone, and you can break into anything. But you aren’t that cool and no one is intimidated by you. If you want to be a cool person, you could also learn Rust. It’s fine. People who like Rust like it a lot. A LOT. It can be creepy. But it is a fine language that gives you slightly less control in exchange for being more friendly to the people who write programs. Maybe too friendly, like a protocol droid. (There are also weird variations on C that exist for niche programming, like C# and Objective C. They aren’t a place to start, more like a weekend in Vegas that you might tell stories about later, but never that story about that thing that happened that one time at that place. We never talk about that.)

If you pick Option 2, you could save yourself years of pain and just learn Erlang. It is hard. It has esoteric syntax (compared to most other languages). It is unlike most other languages, because it was made to make networks, specifically to make the operating systems for telephone switches. Lots of companies used C to write their operating systems for telephone switches and Internet routers and then other companies used C to write programs and operating systems to help make the first group of companies’ devices scale and share information and be resilient to attacks or outages or the need to apply upgrades. Collectively, those companies are worth billions of dollars and employ hundreds of thousands of people. And the Internet is more fragile and less functional than if they all had just used Erlang. If you learn Erlang, you will be like a Mandalorian; people will be intimidated by you because they don’t understand how you do it. They will be afraid of what you can do because it seems too easy to be that powerful. They will wonder if you are an android or an alien or a time traveler. If you find someone who isn’t afraid or intimidated by you, they will probably have a job that will pay the bills (and then some). If you don’t want people to think that about you, but you still want to have the power of Erlang, you should learn Elixir. It is a language with normal syntax that compiles into instructions that the Erlang virtual machine will understand. You don’t get to be a Mandalorian, but also people don’t run away when you come to town and there are more jobs.

If you pick Option 3, you don’t have any choice but to learn LISP. You will pretend that you have a choice and waste years, even decades, learning Java or Ruby until one day, hopefully before you are on your death bed, you will have an epiphany and realize that you have been wasting your time and talents writing software that will fail when the first weird, multi-variable anomaly shows up and that then you will spend long, long hours trying to understand why your code failed, the cold sweat of inevitability pouring down your back as you try to fight back the little voice in your head whispering, “You should have learned LISP”. If you repent early enough, you will become a Jedi, known by your parenthesis, but defined by the clarity of thought and elegance of design that only a language designed for building electronic brains and exploring the stars can bestow. People will think you are a wizard because they can’t imagine that solving hard problems and dealing with uncertainty could be so easy. The Mandalorians will buy you drinks at the bar, which is good, because only other Jedi will give you a job, and it probably will only just pay the bills. If this is the option you want to pick, learn Common LISP because it will train your mind to think properly. If you also want to pay the bills, learn Clojure. On the other hand, if you wait too long, the madness will overtake you and the darkness will consume you and you will find yourself writing JavaScript and muttering to yourself about how the ecosystem is so powerful and ignoring the monstrosity being woven by your own hands as you are consumed, like a programmer version of Smeagol becoming Gollum.

That’s it, these are the languages that I can, in good faith, recommend you spend the time and energy to learn as your primary weapon: C/C++/Rust, Erlang/Elixir, Common LISP/Clojure. There are a bunch of other languages that you might have to learn along the way, like a shell scripting language, SQL, Go, R, and Python, but you should think of them as secondary tools that help you use your primary tools better, not as equals of these ultra-languages; they are the supporting cast to your hero.

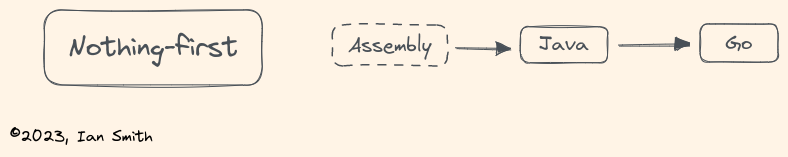

** N.B. — There is a fourth option, but it is the sad divorcee living in a crappy apartment and working a soul-crushing job version of the story. There is no hero, there is no happy ending, and there is no light at the end of the tunnel. You pick this option because you need a job and you have either given up on life or you believe you are strong enough to maintain a bulkhead between the pit of despair that is your employment and the rest of your life. This option, Option 4, ignores the question of what to put in the primary position of importance. The languages in this option aren’t bad, in fact they are pretty good, but they aren’t better in any of the other three Options than what is recommended there, and if you make the decision about what is most important, you wouldn’t pick them without some kind of external constraint that forces you to choose a lessor tool. Typically you end up in Option 4 because the software doesn’t matter, because the problem it is solving doesn’t matter, and the only reason the software exists is because it is put to work work to commodify and dehumanize a part of a business to increase profits. Refusing to make a choice about what is important when abstracting the world is a fantastic sign that the only thing that is important is money, and that means you, your team, your product, and your customer aren’t. You deserve better than to be a means to the end for an already rich and powerful person getting richer and more powerful. If you find yourself here, you should get out, now. Stop reading the Internet and start finding a less corrosive way to pay the bills than writing enterprise software for legal-persons in their wage-slave code factories. Sell your blood, dig ditches, make ASMR videos, panhandle. Just escape and save your soul. Or build bigger bulkheads; summon your inner Atreyu and fight against The Nothing for as long as you can.